I spend too much time on this site. This would likely be fine, if I had a monotonous job that I could compartmentalize; however, I’m a college student.

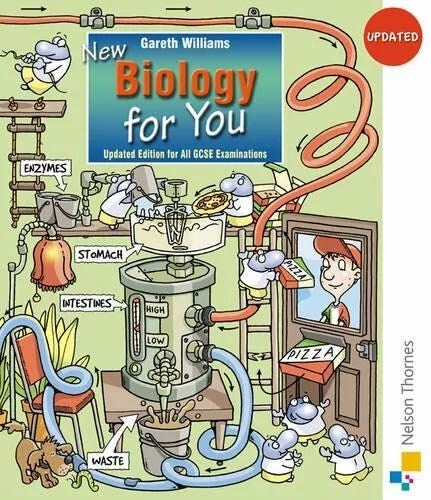

Not only that, but I’d like to pursue STEM, which I think requires a fair amount of rigor—I know, there’s some tongue-in-cheek joke about “women in STEM”, but I was interested in that field before it was cool. Discovering my sister’s high school biology textbook at the age of eight led me to realize that there was much more to the world than I knew. There is so much to know. Although this quote isn’t from a biology textbook, it’s always stuck with me:

“Until the twentieth century, reality was everything humans could touch, smell, see, and hear. Since the initial publication of the chart of electromagnetic spectrum, humans have learned that what they can touch, smell, see, and hear is less than one millionth of reality.”—Buckminster Fuller, 1979

Yet, my enthusiasm and curiosity for everything meaningful or productive seems to have evanesced to a significant degree, and I find this worrisome. It’s reminiscent of how I felt a long time ago, so here’s another Notes entry from August, 2023 (junior year for me, the first unmarred by quarantine):

I think of those times I scoffed at the students who wrote elaborate flashcards, and began preparation for a test a week in advance. That’s a stretch—they began preparing a few months in advance, consulting the school syllabus for what they’d need to learn before the year began.

In actuality, my bravado was a facade for the fact that I couldn’t stand to be disappointed after trying my best; my self-worth was inextricably tied to my perception of my intelligence. Yet, if there was another variable I could deem responsible for my mediocrity, perhaps I could protect my ego. To be able to brag that I completed an assignment in one night and got the highest grade seemed to be the badge of honor to me. This, of course, with taking the most difficult courses possible; it would prove to me that I had the courage to take a risk of faring poorly in a challenging course, and that I could do well without time invested, which can clearly be attributed to my innate intelligence—if I couldn’t, well, that only meant I hadn’t tried enough; my teachers’ report cards, which reiterated how much potential I had if I tried, had only emboldened this thought process. These words seem laughable to me now, but only because I have the privilege to distance myself from the state of my mind at that time. Only because I can once again find the beauty in a world half-full. Only because the last two years seem to be a nightmare that I’m glad to have woken up from.

Now I think of the child I was. Eight-year-old me read my sister’s high school IGSE biology textbook; the awe and fascination with which I read that book hadn’t regarded any status—I didn’t care if people in my class thought I was the smartest. With such zeal and fervour, I had shared every tidbit I learned; this earned me quite a bit of irritation from my teachers (apparently, teachers don’t enjoy it when you ramble about how scabs form, when you’re meant to be filling in sentences with “these” and “those”).

Of particular interest is this reference to scabs. There are fun facts about how the average person replaces all their skin cells every few weeks, so even if they’re not continually scraping their knees, they are growing new skin. However, if I didn’t care about extracting some allegorical or transcendent significance from everything (as convoluted esoteric as it may be), I wouldn’t be writing on Substack, would I?

Similar to literal renewal of the skin, there’s a dynamic component to existence itself, even if our trajectories for various pursuits—such as knowledge—are asymptotic. However, as the best song off of Incubus’s S.C.I.E.N.C.E. album implies, new skin requires the death of old skin, if not a wound to grow over:

Dead skin will atrophy itself to start again

Look closely at the open wound

See past what covers the surface

Underneath chaotic catastrophe

Creation takes the stage

Part of this post is a chronicle of my realization that my reluctance to, well, die, is equivalent to an insect refusing to molt and outgrow its obsolete exoskeleton.

Sunbeams on the Apple Tree

At the time, I had to change schools. This new one was of better quality, while the previous one was where the delinquents went. The latter was apparently run by a Swedish guy, but the quality of its facilities was very lacking, there was a classmate who really enjoyed hitting me1, and the teachers may as well not have existed. The education was of such sparse quality that I was considered the smartest kid in class, to the point that another one of my classmates told me that I had to act less knowledgeable than I was so that he’d seem smarter (he did not want to be outshined by a girl).

During the admissions process, I remember having to visit the office on two occasions. On the second time around, I took a nap after returning home, and woke up the next morning. I really hated it when that happened; I missed out on all the fun, I’d think to myself. I became a bit hostile to the idea of changing schools, because seven-year-old me associated it with this darned experience—there I was in the admissions office, sulking and belligerent, but despite my best efforts, I got in.

I was never a “cursive and highlighters” kid in class, though not for lack of trying. I’d start off the year trying to inculcate the habit, and halfway through, it would just seem like busywork to me. However, I always struggled with making friends, and some of our classes were sex-segregated—I didn’t get along because I was lame, a couple of them had it out for me, and I ended up wanting to be “not like other girls”.

Fortunately for my bored self, I’d read grammar books, astronomy books, essentially what I could comprehend. Once I ended up reading a book about heaven and hell, and that scared me to death (teehee), but a year into my new school, another one of these books was my sister’s (six years older than me) high school biology textbook: New Biology for You by Gareth Williams.

It sounds funny to say that reading that book precipitated a paradigm shift. I wasn’t miserable before, but this was the epitome of my realization that this school did have something good about it—while there weren’t any kids who’d be inclined to scratch my forearm, it’s always taken me a long time to appreciate any change in circumstances. Yet, the book was so riveting to me. There was a sense that I was uncovering some kind of mystery, even if there were vast oversimplifications in the book. I now had something to talk about, even if I never came across as a 500 Days of Summer “I love the Smiths” person (instead seeming more like, well, me).

Did you know that harmful bacteria and viruses are known as pathogens? Did you know that a very high predator-to-prey ratio will be bad for the ecosystem? Did you know that there are dominant and recessive genes?

At a young age, guys tend to be similarly insufferable, talking about Far Cry Go, Minecraft, and other video games I've never played. Conversation-wise, as long as you could out-outlandish them, all was fair game. However, the guys had a “cooties” mindset, partly as—from my experience, at least—what often occurs in actually somewhat patriarchal societies is that it’s nigh-impossible to divorce people from gender roles. If you’re a girl who likes blue, your very existence is an act of rebellion, because everyone knows that girls can only enjoy pink ball gowns and cheesy princess movies! Ewwww! This is why I loathe the modern and ostensibly progressive distinction between biological sex and gender—a woman realizes that she does not resonate with every feminine quality ever, and concludes that she is not a woman after all. Had we only cared about biological sex, we’d realize that she’s still a woman, just not a caricature of one. Alas, we did not, and so we were yet to outgrow the stereotypes.

At the time, I was considered intelligent enough to excuse being a girl for the most part—after all, one could talk to me about National Geographic (it was my favourite TV channel) shows, and I had a bit of an anti-prissy attitude. I was still a nice and reverent student, and the teachers who implemented religious lessons never had any problems with me. Still, I’d joke around in class, often being able to out-outlandish a lot of other students, even if I wasn’t very funny. This was until we had a talent show (I was eight at the time), and then the guys said that I can’t join them, because they were covering Maps by Maroon 5, and there were no girls in Maroon 52. These guys were my friends—how could they disown me for being a girl? I had no control over my chromosomes! It would’ve been better to deem these guys losers and move on with my life, content to be an, ahem, lone wolf, but I really did want friends. As such, “not like other girls” soon morphed into “I might actually be a guy”, and I spurned a lot of the feminine traits I did hold. I have to have low agreeableness. I have to be aggressive. I have to be “tough”. I have to become a guy in the future.

I’m very fortunate that I didn’t grow up in a time that glorified that ethos, as I held this conviction until I was 10 or so, later realizing that I wasn’t a pathological anomaly for not being in complete accord with every other girl ever. There is no such thing as being in complete accord—no matter the trends we ascribe to every collective (“women/men tend to act in such-and-such manner”), there’s significant variance so as to allow for meaningful individuality. On that note, it’s interesting to me that the decline and derision of the “not like other girls” phenomenon has corresponded to greater rates of gender transition, but that’s a topic for another time, even if I find it a bit ironic that it’s occurring in places that wouldn’t be deemed patriarchal by most reasonable people—the popular consensus gleefully declares that “gender is a social construct”, following it by deeming that one’s biology must be calibrated to some desired social affinity. Why not just discard the construct, and remain tethered to the male/female distinction? Perhaps if we were to realize our capacity for individuality, we wouldn’t be so inclined to find a collective to identify with.

What irks me about the prevalence of “girlhood essays” (apart from my usual inability to resonate with them) is the exaltation of the collective, costing the individual’s iconoclastic and idiosyncratic experience. To be completely honest, I’ve usually been unable to resonate with any such essay. Simone de Beauvoir is a bit lame3, and more importantly, Ted Kaczynski is a lot cooler than Ted Bundy4. I don’t want to curate my existence through the lens of being a girl / woman. I want to be a meaningful person in my own right, on my own merits.

Part of this relates to the trade-off between defining yourself and making yourself, and I think that’s what learning allows. It forces you to rest your desire for self-definition for a second, allow information to enter your mind, and exude dedication. It’s this exchange that culminates into someone’s growth; you need to imbue yourself to the task, being transformed in some way, part of your old self dying, a new part being born. In that manner, I too want to break away the shackles of the past, the current illusion of self that I’ve rationalized myself into.

It’s Time For You, To Make a Sacrifice

One of the problems with preemptively trying to define oneself is that it incentivizes a collapse of a superposition of possibilities into a concrete and static image that can be digested and regurgitated at will.

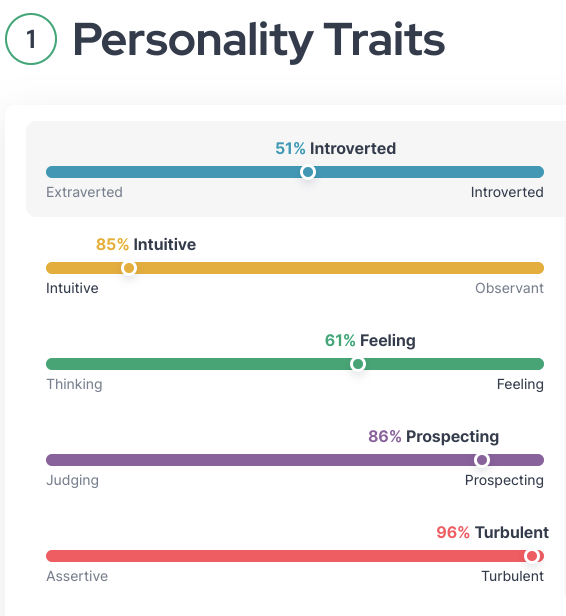

Try to describe your personality. I’ll do mine:

See, there have undoubtedly been times when I haven’t been intuitive, feeling, prospecting, or turbulent. If I were to describe myself as any of these traits, and fully believe them, I’ve already drawn the lines into which I should colour myself. To act in a more observant, thinking, judging, or more assertive manner is deemed anomalous, not in accord with my usual conduct. I’ve inadvertently created a confine for my actions. Yet, definition is temptation, because we live amidst contingencies that we could never fully comprehend into something manageable—to fully experience things as they are is more intimidating, compared to filtering them through the limits of my comprehension. Let’s use an example:

How do I predict where the lone pairs are on the Lewis structure?

I learned this in high school, but it was a bit difficult for me to understand the first time around, and didn’t practice it accordingly, so it’s a weak spot in my understanding of chemistry. Yet, I can step back, lament how this other student can likely understand it all the first time around, or how I must have an irredeemably low IQ. Perhaps I’m not incisively intelligent, perhaps I’m relegated to being a “dumb but diligent”, affable student.

Kind.

To be candid, I’m likely not even kind, but covertly narcissistic and parasitizing off of the high I get from having my ostensible altruism affirmed by others—even assuming that I truly was, kindness is one of those qualities that are valued through eulogies or mission statements. Our thoughts are compartmentalized into emotions of pity, but ultimately, people still want to watch House, MD.

That’s the cathartic reality that Flowers for Algernon points out, to me anyways. In short, Charles Gordon undergoes a surgery, increasing his IQ to unforeseen levels (he could definitely appreciate Rick and Morty). Prior to this, he was mentally disabled, and while this is where we differ, the overall dichotomy and ensuing trade-off between pro-social kindness and cerebral capability has always stood out. Kindness isn’t inherently expedient in the same way as intelligence, which is a tool through which one can advance themselves to unforeseen heights (whether it be academically or vocationally).

This digressional and solipsistic train of thought and downward spiral is where I’m stepping into as I step away from the concrete objective, and this is a bastion of surety. In comparison, the Lewis structure is a looming well of uncertainty, screaming out to me that I’m stupid, the only hope being if I simply were to “not try”. After all, lack of conscientiousness doesn’t devastate me, as would a lack of intelligence.

Duuuuude, I looked at the slides two minutes before the test, I don’t even know what I’m doing but I don’t expect to do well!

This is the comfort. It’s like drinking old cold soup instead of making something new because at least you know the recipe of this one, and you’re afraid of the stove and the ingredients on the counter.

At the end of the day, I’ve still stepped away from Lewis structures. Not only am I spurning the opportunity for the concept to permeate my mind, I’m spurning the part I would’ve dedicated to its mastery. I’ve sacrificed a part of myself, in favour of what I know better than it: all my shortcomings, all my solipsistic “I want”s and “should”s, all of the hypotheses on emotional states and where humanity seems to be going wrong. I know them well, I can elaborate at length, and a couple of peers will mistake it for otherworldliness. I know them well better than I know myself.

It doesn’t need to be Lewis structures. It can be philosophy, theology, history, or some other extremely important topic that I need to dedicate myself to. Meeting the depths of my ignorance forces a kind of reincarnation, but it’s difficult to die in such a substantial manner. I’d rather my death be in the future tense, sometime when I’m in my seventies, unless I—or David Sinclair—figure out a cure for biological aging. Yet, we die in the present tense; I’m not setting a date on my calendar for when I’ll be fine with dying of natural causes—it’s bound to be an interruption.

Sure, we can try to ignore it and make a deal with the devil. In Goethe’s work, Faust makes a deal with Mephistopheles, selling his soul in order to attain unlimited knowledge. Aren’t I doing something similar when I’m refusing to even devote my soul, preferring to cradle the illusion of high-minded thoughtfulness?

Nietzsche would appropriately skewer me as a slave moralist, turning my face away from the prospect of excellence or quality, in favor of a delicate ego, some illusive notion of a clean moral slate. I never sold my soul, the mewling voice cries out. Yet, am I letting it even exist? Even now that I’m in college, it’s taking a while for me to acclimate (as evidenced by some of what I’ve written). I know that I should branch out, join fifty different clubs, spend my days at the library, and hang out with people. Yet, Substack screams,

“Write something, [Ophelia]! Wouldn’t it be nice if you were restacked? One day, everyone will realize how much of a genius you are!”

I don’t know how to remedy this malaise, because there is a continual confirmation that at least when I write here, I’m not completely stupid—even if my only saving grace is that I’m not a Pumpkin Spice somnambulist. In the past, I think I had an implicit incentive to be counter to the prevailing norm, but what do I do when there isn’t some archetype to be counter to? I can’t stand the somnambulists, but I’m not subjected to them such that I can lean into a contrarian force (apart from writing about how I despise college culture)—I’ve mentioned this, but the inclination to be counter is often crucial to individuation.

Part of me wonders, does it even matter if the Pumpkin Spice somnambulists listen to Taylor Swift, or adhere to TikTok or Twitter trends, if they are still meeting their concrete day-to-day demands? If anything, it provides me with the impetus to diminish the importance of the concrete, in favor of being “an esoterically deep thinker, actually”. What does my navel-gazing even accomplish, apart from the illusion of edification?

This Paranoid, Paralyzed Vampire Act’s a Little Old

Again, I’ve delineated angles of this predicament a few times before, both here and in real life—the fear of relegation to affability, of inadequate self-actualization, of being a parasite, of my unintelligence. The chasm between the ambitions I hold and my achievements is threatened to become increasingly pronounced.

What’s the utility in this endless rehearsal, this regurgitation of vitriol? Am I truly digging into some deeper truth? Or is this just some recursive evisceration that serves to neutralize my existence?

The irksome aspect of all this is that I do recognize the importance of my long-term goals, but my immediacy enables a sense of purposelessness to beckon me away from the cross of my life, a sense that’s been solicited by my fears. The importance of the important begins to escape me, as I delve into the solipsistic spiral.

Part of me wants to rediscover New Biology For You by Gareth Williams again—the person I was when I was enamored with it, unfettered by some abstract fear of reflection, emboldened by the infallibility that exists in childhood. I want to be my 8th grade self, reading what I could. I’m searching for the past in order for a future salvation, but how do I know who I was in the past? The zenith of my life trajectory, the period right before quarantine promised me some interpersonal avenue. The period right after required it. In either case, I had better luck talking to my teachers than my peers.

What the best ones had in common was the ability to humanize the intellectual; yet, those were social environments. I don’t have this anymore to the same extent, as Chemistry’s a lecture class with at least a hundred people, but I want to imbue my personality into something. I suppose what I really want to do is embrace the impersonal, whether it be chemistry, philosophy, or whatever—and let it be the stained glass for aspects of myself that I’m continually sacrificing. Perhaps I should start writing informational articles, get out of my own head for a second. Can I humanize the intellectual, instead of attempting to intellectualize my life away?

Whatever the case, past curiosity and its idealistic sanctuary seem so far away to me, but my intuition tells me that the concrete objective needs to be the object in observation. If it’s myself, I know that I’ll board directionless trains of thought—I’ve been told that I’m too self-aware, so I don’t know if self-awareness can still be the panacea to what seems to be approximating apathy. It seems to substitute mental bruxism for action, but why would anyone want to sacrifice their teeth?

Even when I moved schools (and countries!) when I was nine, I became acquainted with a girl who’d shove me around. I never did learn how to get these people to change their behavior, but it stopped before I entered high school.

Indirectly, I thank them for this, as I became incentivized to seek out heavier and less poppy music—ironic that Maroon 5 doesn’t fall into that camp. I’ll also thank bands like Nightwish, Lacuna Coil, and Evanescence for helping me realize that you don’t have to be a guy to create good music.

A classmate wrote an essay about how Canadian author Andrea Munro was justified in forgiving her husband for molesting her daughter. Reason? She was a victim of patriarchal forces that give rise to the “ambivalence of motherhood”. Women’s decisions are the result of societal influences, “one is not born, but becomes a woman”, motherhood is associated with positive connotations which is bad. We had a peer review session, and some girl exclaimed,

“Every girl in this classroom could resonate with your essay!”

No, I couldn’t resonate with such an expedient outsourcing of personal failures to collective abstractions. I think there is a basic level of responsibility as a parent or caretaker, and part of it is caring for one’s children—not forgiving scumbags for taking advantage of them. I despised that essay, but that’s for another article.

Bundy fans are overwhelmingly women and Kaczynski fans are overwhelmingly men. Obviously something to write an article about, but that’s besides the point—I still can’t believe that Kaczynski supplied my senior yearbook quote:

“But what kind of freedom does one have if one can use it only as someone else prescribes?”